Introduction

When you press a key on your Windows keyboard, the input doesn’t immediately appear on your screen. Instead, it travels through multiple transformation layers — a chain that converts raw hardware signals into text, hotkeys, and game commands. Understanding this chain is essential for anyone working with custom keyboards, keyboard layouts, or applications that handle input.

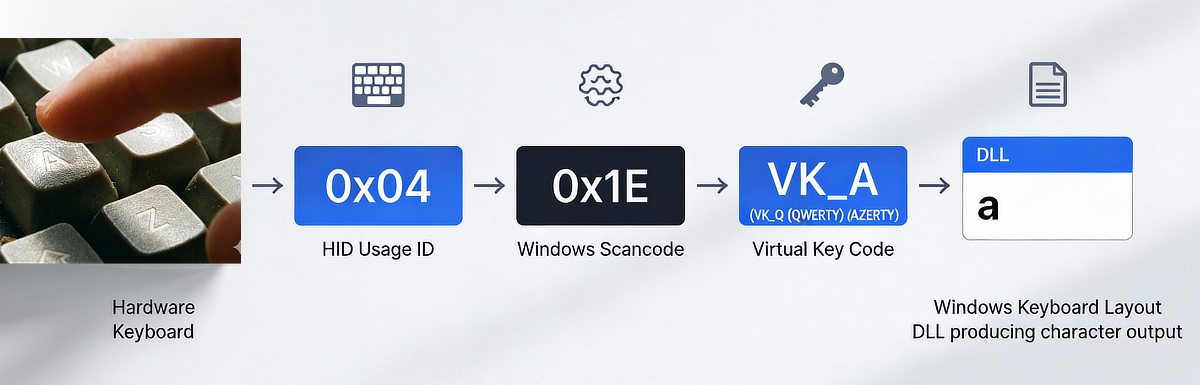

The complete Windows keyboard input chain looks like this:

HID Usage ID → Windows Scancode → Virtual Key Code (VK) →

Windows Keyboard Layout → Character Output / Application Input

But the story is more complex than it appears. Not all applications use every step, and choosing which step to use has profound consequences for compatibility and functionality.

Terminology: Three Distinct Concepts

Before diving into the chain, it’s crucial to clarify three concepts that are often confused because they’re all called “keyboard layout” in casual speech:

1. Physical Key Layout / Position

The physical arrangement of keys on the keyboard hardware.

Examples: ANSI 104-key (standard US), ISO 105-key (European), split columnar staggered ergonomic keyboards (Kinesis Advantage, Lily58 …)

2. Windows Keyboard Layout

The input layout selected in Windows Settings under Language & Region → Keyboard, determining character mapping and Virtual Key assignments.

Examples: US English (QWERTY), French (AZERTY), German (QWERTZ), Dvorak, Colemak

3. Software Remapping Layer

Custom key transformations applied via software tools (such as Kanata, AutoHotkey) that intercept input after the Windows keyboard layout processes it.

Examples: Kanata profiles (e.g. for anymak:END, Graphite), AutoHotkey scripts

Note: QMK or ZMK firmware is different — it operates at the HID level, replacing the standard HID input from a keyboard, not layering on top of the Windows keyboard layout.

The Windows Keyboard Input Chain

Step 1: HID Usage ID (The Transport Layer)

Modern USB keyboards speak the language of HID (Human Interface Device) standards defined by the USB Implementers Forum. When you press the “A” key, your keyboard firmware sends a HID usage ID — specifically 0x04 from the HID Keyboard/Keypad page (usage page 0x07) — over the USB bus.

This is why keyboard firmware like QMK uses keycodes like KC_A: these are symbolic names for HID usage IDs. The HID standard is universal across operating systems, making it the common ground between your keyboard hardware and any operating system.

Each operating system then translates that HID usage according to its own architecture. Windows converts HID to scancodes, macOS has its own mapping, Linux has yet another — but they all start from the same HID usage ID.

Step 2: Windows Scancode (The Position Identifier)

The Windows HID driver (kbdhid.sys) receives the HID usage ID and converts it into a Windows keyboard scancode — essentially a legacy PS/2-era code that identifies the physical key location on the keyboard. Scancodes are truly form-factor-independent and Windows-keyboard-layout-independent; they represent raw physical positions.[1][2]

For example, on a standard ANSI keyboard:

- HID usage

0x04(A key) → Windows scancode0x1E - HID usage

0x05(B key) → Windows scancode0x30

Critical point: Scancode 0x1E always refers to the same physical key position on an ANSI keyboard, the one labeled “A” in the US layout. Regardless of which Windows keyboard layout you activate, scancode 0x1E always corresponds to that same physical location.

Why scancodes do .sexist: Windows maintains decades of backward compatibility with PS/2 keyboard code. Scancodes provide a stable reference to physical hardware positions that doesn’t change when the user switches Windows keyboard layouts.

Step 3 & 4: Virtual Key Code and Windows Keyboard Layout DLL (Linked Concepts)

The scancode is then passed to the active Windows keyboard layout, which is provided as a DLL file (e.g., kbdus.dll for US, kbdfr.dll or the updated kbdfrna.dll for French). This DLL performs two linked transformations:

First: Scancode-to-VK mapping

The DLL maps the scancode to a Virtual Key (VK) code. This mapping depends entirely on which Windows keyboard layout is active.

Same physical key position (scancode 0x1E on ANSI keyboard):

US English (QWERTY) layout active:

Scancode 0x1E → VK_A

French (AZERTY) layout active:

Scancode 0x1E → VK_Q

German (QWERTZ) layout active:

Scancode 0x1E → VK_A

Second: VK-to-Character mapping (with modifiers and dead keys)

The same DLL also defines what character (or function) each VK code produces, including potential modifiers (Shift, Ctrl, Alt, AltGr) and dead key combinations. For this example (Scancode Ox1E) we get:

US layout DLL:

VK_A + no modifiers → 'a'

VK_A + Shift → 'A'

VK_A + Ctrl → (control code, application-dependent, typically "mark all")

French AZERTY layout DLL:

Scancode 0x1E (US-ANSI A-key physical position):

VK_Q + no modifiers = 'q'

VK_Q + Shift = 'Q'

VK_Q + Ctrl → (control code, application-dependent, typically "close window")

Understanding the relationship:

- Scancodes represent physical positions (hardware-level, unchanging)

- VK codes represent which key (semantically) is at that position in the active Windows keyboard layout

- The Windows keyboard layout DLL defines BOTH the scancode-to-VK mapping AND the VK-to-character mapping

The entire chain — from scancode to VK to character — is bundled in the DLL for that layout. When you switch Windows keyboard layouts, a completely different DLL takes over, and both mappings change accordingly.

Why Virtual Keys Exist: The Design Philosophy

You might ask: why not map scancodes directly to characters, or use raw HID usage IDs throughout? Why introduce an intermediate VK layer at all?

The answer reveals Windows’s design philosophy: VK codes allow different applications to choose which abstraction level matters for their use case.

Applications have a fundamental choice:

Option 1: Use Scancodes (Position-Based, Layout-Independent)

- “I care about physical position, not what character it produces”

- Examples: Games (Counter-Strike, Valorant), music software (Ableton), stream decks, accessibility tools

- Method: Use Raw Input API or DirectInput, bypass VK codes entirely

- Behavior: Work identically across all Windows keyboard layouts because they use the physical position (scancode), not the layout-dependent VK

Option 2: Use VK Codes (Layout-Dependent)

- “I care about what key this is in the user’s active Windows keyboard layout”

- Examples: Text editors, system shortcuts, most productivity software

- Method: Use the standard Windows message loop (WM_KEYDOWN, WM_KEYUP, WM_CHAR), work with the Windows keyboard layout system

- Behavior: Automatically adapt to any active Windows keyboard layout

This design choice enables two critical capabilities:

1. Games Work Perfectly Across Windows Keyboard Layouts

WASD movement keys work on AZERTY keyboards as ZQSD — automatically. Why?

Games use raw input or scancode-based input, binding to physical positions:

Game binding: "Physical position 0x11 forward" (using scancode)

US QWERTY keyboard:

Physical position 0x11 has "W" printed on it

Player presses W → scancode 0x11 sent → forward movement

French AZERTY keyboard:

Same physical position 0x11 has "Z" printed on it

Player presses Z (at position 0x11) → scancode 0x11 sent → forward movement

Result: Movement works identically in both cases because both use the same physical position

Games never see VK codes; they only see scancodes (physical positions). The physical position is constant, so gameplay is identical regardless of Windows keyboard layout.

2. One Keyboard, Multiple Windows Keyboard Layouts at Runtime

You can switch Windows keyboard layouts in Settings without touching drivers, restarting, or reconfiguring hardware. The same keyboard works with:

- US English (QWERTY)

- French (AZERTY)

- German (QWERTZ)

- Dvorak

- Colemak

- And dozens of others

Only the Windows keyboard layout DLL changes; the scancode-to-VK mapping updates accordingly; the hardware communication stays constant.

When Different Applications Use Different Steps

Different applications interface with different levels of the keyboard chain, which is why the same key can behave differently in different programs:

Scancode-Based Input: Games and Position-Sensitive Software

Games like Counter-Strike, Valorant, and music software like Ableton Live use raw input or scancode-based input via DirectInput or the Raw Input API.

These applications:

- Receive hardware scancodes directly, bypassing VK codes and Windows keyboard layouts entirely

- Work identically on QWERTY, AZERTY, QWERTZ, or any Windows keyboard layout because they use physical positions

- Allow users to rebind controls to any physical position without layout interference

Why: Games optimize for physical control consistency. A player expects WASD to be in the same physical locations regardless of Windows keyboard layout. The physical location is the contract; the character produced is irrelevant.

VK-Code-Based Input: Some System Hotkeys and Applications

Some applications bind system hotkeys using VK codes. However, this is complicated because the same application might use both approaches.

For example, in hotkey definition dialogs:

- The application often records scancodes when you press keys

- But when processing hotkeys during runtime, it checks VK codes against the active Windows keyboard layout

This creates a problematic gap: if you define a hotkey while one Windows keyboard layout is active, and then switch to a different Windows keyboard layout, the hotkey may not work as expected. The scancode you recorded might map to a different VK code on the new layout.

Additionally, certain software (like Microsoft PowerToys) cannot record hotkeys when a software remapping layer is active, the likely reason is that the hotkey definition field checks the scancode at definition time, while the running application checks VK codes during execution. A remapping layer that transforms scancodes before they reach the definition dialog will appear to send different keys than the hotkey detection system can record, but once the hotkeys are defined, the remapping layer works transparently during runtime because it operates after VK code generation.

Character-Based Input: Text Fields and IME-Aware Applications

Some applications care only about the final output character, not the key code at all:

- Register for

WM_CHARmessages (the final Unicode character after all transformations) - Ignore

WM_KEYDOWNandWM_KEYUPentirely - Work with any input method (keyboard, Input Method Editor, voice-to-text, touch typing)

Why: These applications are text-focused and don’t care how the text arrived. Whether the user typed it, pasted it, or used an IME to compose it, the application receives the final Unicode character.

The Relationship Between Layers: A Complex Reality

The three-layer abstraction (scancode → VK → character) suggests a clean separation, but the reality is more tangled:

Within the Windows keyboard layout DLL:

- The scancode-to-VK mapping is hardcoded for that layout

- The VK-to-character mapping is also defined (including with modifiers and dead keys)

- There’s no separation between these steps; they’re bundled in the DLL

Across different Windows keyboard layouts:

- The same physical key (same scancode) produces different VK codes on different layouts

- The same VK code might not exist on all layouts (e.g., VK_OEM_1 varies)

- Applications assuming consistent VK codes across layouts will break

At the application level:

- Hotkey definition and hotkey execution might use different abstractions

- Some apps record scancodes but check VK codes during execution

- Software remapping layers can interfere with hotkey recording but not execution. This inconsistency can be a source of confusion for users trying to remap their keyboard with tools like Kanata or Autohotkey.

Conclusion

Windows keyboard input is layered. Each layer solves specific problems:

- HID usage IDs provide OS-independent hardware communication

- Scancodes identify raw physical positions (which is why games work across layouts)

- VK codes enable layout switching at runtime without driver changes

- Windows keyboard layout DLLs transform VK codes into characters

However, the abstraction can lead to unexpected behavior or problems in practice:

- Applications mix abstractions (record scancodes, check VK codes)

- Software remapping layers can interfere with some use cases but not others

- The VK-based system works well for text input but creates complexity for system shortcuts and keybindings

The current design enables important features (runtime layout switching, game portability) but also creates the “Windows keyboard input hell” that many advanced users experience. More sophisticated features — like timed input methods, such as layers via hold-tap, autoshift, key combinations (combos), or context-aware keybindings are not available within the Windows keyboard layer system. These require either custom firmware (e.g. QMK, ZMK) or software remapping layers (e.g. Kanata, AutoHotkey), which introduce their own complexities and compatibility issues.

Understanding which layer you’re working with, and which abstraction level your application uses, is the first step toward navigating this complexity. To dive even deeper read the follow-up article covering AltGr layers, dead keys, IME and the different options for keyboard remapping.

References

[1] Microsoft Learn: Keyboard Input Overview

[2] A summary of scan code & key codes sets used in the PC virtualization stack

[3] Microsoft Learn: ToUnicode function

[4] Stack Overflow: Detect if Right Alt generates Ctrl+Alt (AltGr) in current layout