What Layout Analyzers Do Well

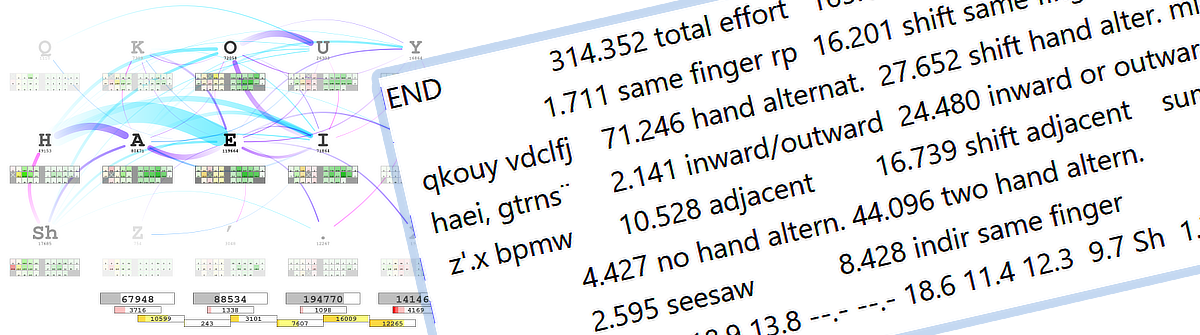

Layout analyzers are powerful tools. They can save many hours of manual work and help to get a good grasp of a keyboard layout much faster than without. They provide objective data of keyboard layout characteristics, such as bigram distributions, which would take weeks to calculate by hand. Some offer additional visual insights such as showing finger paths, heatmaps of finger use and hand alternation charts. They let you compare dozens of layouts against consistent metrics. They’ve helped discover genuinely useful layouts like AdNW, Enthium, KOY and Graphite.

But analyzers have significant limitations. Understanding these limitations is essential before trusting an analyzer’s conclusion that one layout is “better” than another.

How analyzers score a layout

All analyzers try to score how comfortable or easy certain finger movements are. They either provide numbers for some kind of “effort”, where lower is better. An example is the position on the keyboard or how often the same finger needs to press keys. Often analyzers also provide numbers for metrics which are considered to be good. For example alternating hands between keys or inward rolls on a hand are comfortable and a higher number is better therefore. A general discussion of how to rate a keyboard layout is given in the article about Dvorak’s keyboard design principles.

The Three Core Limitations of Layout Analyzers

Limitation 1: Not All “Bad Motions” Are Equal, But Analyzers Treat Them As Equal

Same-finger bigrams (SFBs) are a good example. An SFB on a strong finger (index or middle finger) from the top row back to the home row (like E-D in QWERTY) is fundamentally different from an SFB on a weak finger (ring finger or pinky) from the home row down to the bottom row (like S-Z in QWERTY).

Why the difference? When you press E-D, your finger leaves the home position briefly and returns naturally as part of the next keystroke. The motion still flows. Depending on the key caps you might even be able to “rake” the finger from one key to the other. In contrast S-Z requires your weak finger to stretch down and return to home position – a much more disruptive motion.

What analyzers typically do: Count both as “1 SFB” with equal weight.

What they miss: These motions have different real ergonomic costs. A layout with a moderate amount of higher SFBs might feel better if most of those SFBs are the harmless top-to-home variety.

Real example: For English anymak:END has a higher SFB percentage than some modern layouts (like Graphite). Graphite has 1.1% SFBs (according to ‘opt’ with standard corpus) while anymak:END has 1.7% SFBs. But most of anymak:END’s SFBs occur between the top row and home row on strong fingers (index/middle), the comfortable type. The raw numbers say Graphite is better than anymak:END in regards to SFBs. That is true by counting each SFB equal. But the true efforts are not described granular enough. So you cannot conclude from the single number alone if or by how much a certain layout will feel better or worse.

The same issue applies to scissors (two-finger twisting motions). Q-S in QWERTY is worse than A-W, but most analyzers count all scissors equally. A layout with more scissors might feel better if they’re all low-impact combinations. Some scissors “on paper” might actually feel pretty good in reality. An example would be E-F in QWERTY.

The solution analyzers miss: We would need a table rating all possible finger-pair combinations by their actual ergonomic cost. This is doable but would require psychophysical experiments (testing with real typists under controlled conditions) to validate.

Limitation 2: Metrics Are Combined Without Understanding Their Relative Weight

Layout analyzers typically measure multiple metrics: same-finger bigrams, hand alternation, inward rolls, outward rolls, scissors, distance traveled, etc. They often those are combined into a single “effort score.”

The problem: We don’t know how much each metric actually contributes to how good a layout feels. Also the next step – how combined finger-motions (bigrams or trigrams) – are interacting is not really understood now.

Example: Analyzer X weights SFBs at 30%, hand alternation at 25%, scissors at 20%, and other factors at 25%. But who decided on those weights? Did someone test it with real typists? Or was it a guess?

The mathematical consequence: Imagine an analyzer says Layout A has 2.3% total effort and Layout B has 2.1% effort. The conclusion seems clear: Layout B is better by 0.2%.

But here’s the problem: If the underlying uncertainty in measuring these metrics might be ±3.8%, then the difference of 0.2% is noise, not signal. We’re measuring a door’s width to 0.1mm precision when our tape measure has ±1mm error. The apparent difference is meaningless.

Why we don’t know the weights: We would need psychophysical experiments with trained and possibly also untrained typists to determine how much each metric actually matters. Do typists notice a 0.5% reduction in same-finger bigrams? Do they notice a 1% improvement in hand alternation? By how much? These are empirical questions, not mathematical ones.

The current situation: Most analyzers use educated guesses for their weights. These guesses might be reasonable, but they’re not validated. Layouts optimized against these guesses might not actually feel better in practice.

The practical consequence: When two layouts are numerically close (and we do not know yet what “close” means for a specific analyzer score) do not trust to be better alone by the numbers. Test both by typing real text. The difference in “effort score” can be below measurement uncertainty. What you can do is to compare different layouts in regard to a single metric and get a basic idea how they perform for that single parameter – nothing more and nothing less.

Limitation 3: Layer Switches Are Completely Ignored but They Are Crucial

Layout analyzers examine the character positions of the base layer (where all the letters live). They mostly ignore one of the biggest ergonomic factors: where your modifier and layer-switch keys are placed, and how they’re implemented.

Why this matters: In typing:

- Shifted characters (capitals, symbols) require a layer key (Shift)

- Language-specific characters (umlauts in German, accents in French) often require a layer key or dead key

- One-shot vs held layer keys (tap vs hold) change the ergonomic cost dramatically

- Auto-Shift, Combos or other timed approaches to switch to layers are not considered

Example 1: Shift placement and One-shot vs held modifiers

In QWERTY, Right-Shift lives on the pinky at the bottom corner – exactly where your pinky has to stretch quite far and you possibly need to twist your hand uncomfortably. For English, this is annoying already. But for German, where capitalizing words is very common, Shift is in heavy use. The pinky strain adds up even more. On an ANSI-keyboard the Left-Shift key is much easier to reach, by just curling the pinky inward a bit. On some keyboards, with nicely sculpted keycaps, that finger motion can even be a comfortable one. So it is crucial to take the position of the shift-key into account and weigh the efforts accordingly.

A unique characteristic of anymak:END is moving Shift to easy to reach positions. By populating the /-key (QWERTY) with shift, the problem described above gets resolved. In addition shift is a one-shot key on both hands, which minimizes SFBs with character-keys and the shift-key.

When you hold Shift while typing a capital letter, your hand is in a constrained position. You can’t move your hand naturally while Shift is held. When you use one-shot Shift (tap Shift, and the next keystroke becomes capitalized), your hand is free to move between each keystroke. This is more comfortable and feels faster.

Both the more comfortable finger placement and the decrease in SFBs due the one-shot function are real world advantages, but become not visible in many analyzers because they don’t examine layer key placement, nor know if you use one-shot layer switching or not.

Example 2: Language-specific costs

For English, Shift is used occasionally. Optimizing its placement is important but less critical than for other languages.

For German, where many words are capitalized, Shift placement becomes an even more important ergonomic factor. A layout optimized for English (by an analyzer) might feel more uncomfortable for a German typist who uses Shift constantly.

For Hungarian, with heavy use of diacritics and multiple layer-switch keys, the position of all layer keys becomes crucial. An analyzer ignoring layer (or dead-key) placement will produce a layout that feels awkward in practice.

The current gap: Layer-key placement is huge optimization space that most analyzers completely ignore. It’s not a minor issue and has a serious impact on how the layout will feel in everyday use. This is true for English users and even more so for many other languages.

Example 3: Magic Keys and Context-Dependent Optimization

Some layouts like Magic Sturdy use “magic keys” — special keys that intelligently modify the output of adjacent or previously typed keys based on context. Unlike layer keys (which change which character set is available), magic keys optimize specific keystroke sequences by producing alternative characters based on what was typed before or the hand context.

For example, a magic key might intelligently handle a common bigram that would normally be an SFB or awkward redirect, producing the right character while reducing finger strain.

What an analyzer sees (if configured):

Analyzers can be configured to account for magic keys by pre-computing their likely outputs and including those patterns in the analysis. The analyzer can then measure whether the magic key’s intervention actually reduces SFBs, improves hand alternation, or eliminates awkward redirects. If properly configured, the analyzer can account for magic keys as a design tool.

What the analyzer still misses:

- Cognitive load: Magic keys trade finger ergonomics for mental load. Even if the keystroke sequence is physically easier, your brain must recognize and trust the context-aware behavior. Will you consciously think about whether the magic key will trigger, or will it become automatic? This varies by person and by how intuitive the magic key’s logic is.

- Learning curve and reliability: A layout with many magic keys requires learning when they activate and trusting that they’ll do the right thing. Some typists find this second nature; others find the unpredictability frustrating or fatiguing, even if the physical metrics are better.

- Individual preference for predictability vs. optimization: Some typists prefer “what you press is what you get” (traditional keys) even if it means slightly more effort; others prefer optimized-but-conditional behavior. This is a design philosophy choice, not a measurable ergonomic factor.

The practical consequence: An analyzer can show that magic keys reduce SFBs or improve alternation numerically, but it can’t predict whether the cognitive overhead will outweigh the physical benefits for you. A layout with excellent metrics but many magic keys might feel slower or more mentally taxing than a layout with slightly worse metrics but more straightforward behavior.

The lesson: Magic keys are a powerful optimization lever, but they represent a trade-off between physical ergonomics (measurable) and cognitive ergonomics (not measurable by analyzers). You must test these layouts with real typing to know if the trade-off works for your brain. The analyzer can help validate that the magic keys are actually improving the intended metrics, but it can’t evaluate whether you’ll prefer that optimization style.

Why Limitations Exist: The Structure of Analyzers

These described limitations do not exist in isolation. They come on top of other challenges:

The Corpus Problem

An analyzer needs a text corpus (sample of writing) to analyze. But different corpora produce different “optimal” layouts:

- Typing test corpus (common words, balanced): Produces layouts good for general typing

- Programming corpus (lots of symbols, brackets, semicolons): Produces layouts that prioritize symbol access

- German corpus with many capitals: Produces layouts where Shift/layer placement optimization becomes more important

- Prose corpus: Might de-prioritize symbols and focus on letter frequency

The consequence: An optimizer produces a layout that’s optimal for that specific corpus – not necessarily for your actual typing. If you code 50% and write mails and messages 50%, but the analyzer only trained on prose, the result might feel wrong for your use case.

The Hardware Variability Problem

Analyzers often assume a standard ANSI or ISO keyboard with row-staggered keys. But keyboards vary:

- Row-staggered (standard): Key columns are offset by rows

- Column-staggered (ergonomic split keyboards): Key columns are aligned vertically. Column-staggered keyboards differ significantly in the amount of stagger.

- 3x5 vs 4x6 + 2 or 3 or more thumb keys Ergonomic split keyboards often come with a base grid (per side) of 3 or 4 rows and 5 or 6 columns. In addition they offer one, two, three or sometimes even more thumb keys per side. Which of those keys do you use for characters, which for what kind of layer switches?

- Keycaps, Key Size and Switches How large are the thumb keys? Where are they placed in relation to the hand? Do the keys use MX or Choc or another spacing? Even the keycap shape has an influence which keys are how comfortable and precise to use.

- Nontraditional keyboards Svalboard and other keyboards – how to map these input methods to an analyzer?

- Hand size variation: What’s reachable for one person might require stretching for another.

The consequence: A layout optimized for one hardware type might feel less natural on another. The “optimal” finger reach differs between hardware designs.

anymak:END’s solution: It was specifically designed to work on both standard row-staggered keyboards and split columnar-staggered keyboards with moderate pinky stagger. Not using the ANSI B-key position was a necessary hardware-compatibility requirement to maintain the same comfortable fingering on both a standard and a split ergo keyboard. But even in that case the analyzer will not fully reflect the actual efforts, when it is not configured to take into account the exact key positions and the efforts for the hand size of the user in question.

The Search Algorithm Problem

Analyzers use algorithms (usually simulated annealing or genetic algorithms) to search the space of possible layouts. But this search has limitations:

- Local optima: The algorithm might find a good layout that’s not the best layout. Imagine a landscape of hills; the algorithm might climb a tall hill and think it’s found the peak, missing the actual highest mountain nearby.

- Search space is huge: With 47 keys and tens of thousands of possible bigrams, the search space is enormous. Perfect optimization is computationally infeasible.

Practical consequence: Optimizer-generated layouts are usually good starting points, but they’re not guaranteed to be globally optimal.

How Context Factors Interact: A Practical Example

Let’s trace how these factors affect two different layouts:

Graphite:

- Corpus: Optimized for modern English typing

- Hardware: Works on standard ANSI keyboards

- Metrics: Low SFBs (1.1%), excellent hand alternation, good rolls

- Layer consideration: Standard Shift position

- Result: Feels good for English typing; less ideal for heavy capital use or multiple languages

anymak:END:

- Corpus: Optimized on equal weighting of English, German, and Dutch

- Hardware: Designed to work identically on both row-staggered and column-staggered keyboards

- Metrics: More SFBs than Graphite (1.7%), but mostly the harmless top-to-home type; excellent hand alternation but still many inward-rolls; strong-finger prioritization

- Layer consideration: One-shot layer keys in comfortable position, symmetrical left-right placement, B-key position (QWERTY) on ANSI/ ISO not used for hardware compatibility

- Result: Comfortable for multi-language typing; Shift-heavy use (German) feels better due to one-shot optimization; works on any keyboard; more SFBs but less finger effort, due avoiding harder to reach keys.

The lesson: No analyzer can capture all these factors simultaneously. A layout’s quality depends on how well it matches your corpus, your hardware, your layer use, and your typing patterns.

How to Use Analyzers Wisely

Given these limitations, here’s how to get genuine value from layout analyzers:

1. Use Analyzers for Exploration, Not Gospel

Run an analyzer on a few layout variations. Use the graphical output (finger paths, heatmaps, hand alternation charts) to understand the visual differences.

Don’t obsess over the raw “effort score.” The finger path charts from opt are an excellent addition to the numbers.

2. Compare Across Multiple Metrics Separately

Instead of trusting a combined “effort score,” compare individual metrics:

- How many SFBs, and where are they? (Top-row-to-bottom-row SFBs are less of a concern.)

- What’s the hand alternation? (Higher is always better)

- How many inward rolls? (Higher is better too)

- How many scissors, and what type? (Pinky scissors are worse than index-finger scissors. It is relevant which finger is up and which one down.)

- How many redirects – especially on weak fingers?

Keep these separate. A layout strong in one area might and often will be weaker in another, but that trade-off might suit your typing better. In the end the search is not for the perfect layout – which can not exist – but for a good balance of different criteria. Some being more important than other. Yet, we do not know the absolute “best weighting” of those for now.

3. Remember the Corpus Matters

If you’re optimizing for programming, use a programming corpus. If you’re optimizing for German writing, use German text with proper capitalization and umlauts. Make the corpus large enough. The manual from the opt analyzer has a section on how to find out if the corpus is large enough.

4. Factor in Layer-Key Placement Manually

Analyzers ignore this often, but you shouldn’t. Ask yourself:

- Where are my Shift/layer keys?

- Are they one-shot or held? Or do you use another way to enter layers, such as autoshift or combos? Or do you use home-row-mods for shift?

- Are they on weak fingers (pinkies) or strong ones (index/middle) or on the thumb? How comfortable are they to reach?

- If I type heavily in a language with capitals or diacritics, is layer placement optimized for that?

This is optimization space the analyzer might be missing. You can and should take that into account in some way.

5. Test Similar Layouts Practically

When an analyzer shows two layouts as nearly equivalent numerically, don’t try to pick based on small differences in effort score. Instead:

- Try both layouts with a simulator program, where you use the keyboard layout you already can use, to translate the layout in question to

- Type real text you care about. The most used words in a language are a good start. It is also worth to have a look at some especially “ugly” words to type for the layout in question. You can find hard to type words in the analyzer from Cyanophage.

- Notice which layout feels more natural for which words and how many. Pick the layout that feels better overall. Your hands know better than the metrics.

6. Use Analyzers to Understand Trade-Offs, Not to Crown a Winner

When you have a shortlist of 2-3 layouts, use the analyzer to understand what each layout prioritizes:

- Layout A optimizes for hand alternation but has more SFBs

- Layout B minimizes SFBs but uses more same-hand patterns

- Layout C prioritizes inward rolls at the cost of some distance

This understanding helps you predict whether each layout will feel good for your hands and typing patterns. The numerical “winner” might not be the best choice for you.

7. Consider What Hardware It Was Designed For

If it was optimized for one keyboard type, some optimizations might not transfer to your hardware. If possible change the configuration file to reflect your actual physical key arrangement so you get a meaningful evaluation result.

8. Verify How Metrics Are Weighted

If the weights are guesses, the overall effort score is less reliable. Potentially check the weightings – for example of the finger efforts for each key position – and verify and update as needed if those relate to your personal estimation if one key is harder or easier to reach than another.

Analyzer Limitations in Practice: Real Examples

Example 1: Graphite vs anymak:END

An analyzer might show:

- Graphite: Fewer SFBs (1.1%), excellent hand alternation, optimized for English

- anymak:END: More SFBs (1.7%), similar hand alternation, optimized for 3 languages

Raw verdict: Graphite is slightly better for SFBs; they’re roughly equivalent on hand alternation.

But what the analyzer misses:

- Graphite’s Shift is standard (pinky on ANSI keyboard); anymak:END’s Shift is optimized for one-shot in comfortable to reach spot

- Graphite was optimized for English; anymak:END was optimized for equal English-German-Dutch use and works well with French and Spanish

- anymak:END works on both standard and columnar-staggered keyboards with identical fingering

- If you type German 40% of the time with frequent capitals, anymak:END’s Shift optimization is a huge practical advantage that raw metrics from many analyzers don’t show

The lesson: Analyzer metrics are comparative but not absolute. They show relative trade-offs within a narrow context, not which layout you’ll actually prefer given your actual use.

Example 2: Enthium (Thumb-Character Layout)

Enthium is an unusual layout that puts common characters on thumb keys instead of finger keys.

What an analyzer sees:

- Lower distance traveled (thumb keys are accessible)

- Different SFB/alternation patterns

- Maybe lower “effort”

What the analyzer misses:

- Thumb keys require hardware support (split keyboard, thumb cluster) - layout can not be used with a standard keyboard, such as a laptop

- Learning curve is high (thumb placement is very different from standard finger-based typing)

- Not all thumbs are equally strong; thumb-heavy use has different ergonomic characteristics than finger-heavy use, some people get problems when using thumb-heavy layouts

Raw verdict: Analyzer says Enthium is efficient; in practice, depends entirely on your hardware and willingness to relearn fundamentally.

The lesson: Layouts still require human judgment. Analyzers can’t evaluate them fairly in completeness.

What Makes a Good Analyzer?

After understanding these limitations, you might wonder: what would a better analyzer look like?

A more complete analyzer would:

-

Weight metrics empirically. Conduct psychophysical experiments with real typists to determine how much each metric actually affects comfort and speed.

-

Support multiple corpora. Let users train on their actual typing patterns, not just generic text.

-

Account for hardware. Allow different optimization for row-staggered vs column-staggered, or even custom reach maps based on hand size.

-

Include modifier placement. Treat Shift, layer-keys, and one-shot vs held as part of the optimization, not afterthoughts.

-

Estimate uncertainty. Report not just a score, but the confidence interval around it. “Layout A is better with ±2% uncertainty” is more useful than “Layout A is 0.5% better.”

-

Provide trade-off analysis. Show “Layout A wins on hand alternation; Layout B wins on SFBs” instead of combining them into one opaque score.

Current state: No analyzer does all of these. The ‘opt’ analyzer does some of them reasonably well and offers extensive documentation and customization options, but even it has some of the limitations discussed here.

Conclusion: Analyzers Are Guides, Not Oracles

Layout analyzers are genuinely valuable tools for exploring the keyboard-layout space. They save massive amounts of time and catch obvious problems (like a layout with tons of same-finger bigrams).

But they’re not oracles. They can’t tell you which layout you’ll actually prefer. They can’t account for your specific hardware, your actual typing patterns, your layer-use intensity, or your language needs. They usually do not measure layer-key ergonomics.

Use them as guides:

- Explore multiple layouts and understand their trade-offs

- If possible use the finger-motion diagrams from opt in addition to the numbers

- Test similar layouts by typing, not by comparing scores

- Remember that analyzer gaps exist, so test practically

Then trust your hands. The best layout is the one that feels best when you type it.